|

|

|||

|

By Staff Sgt.

Guy Volb 374th Airlift Wing

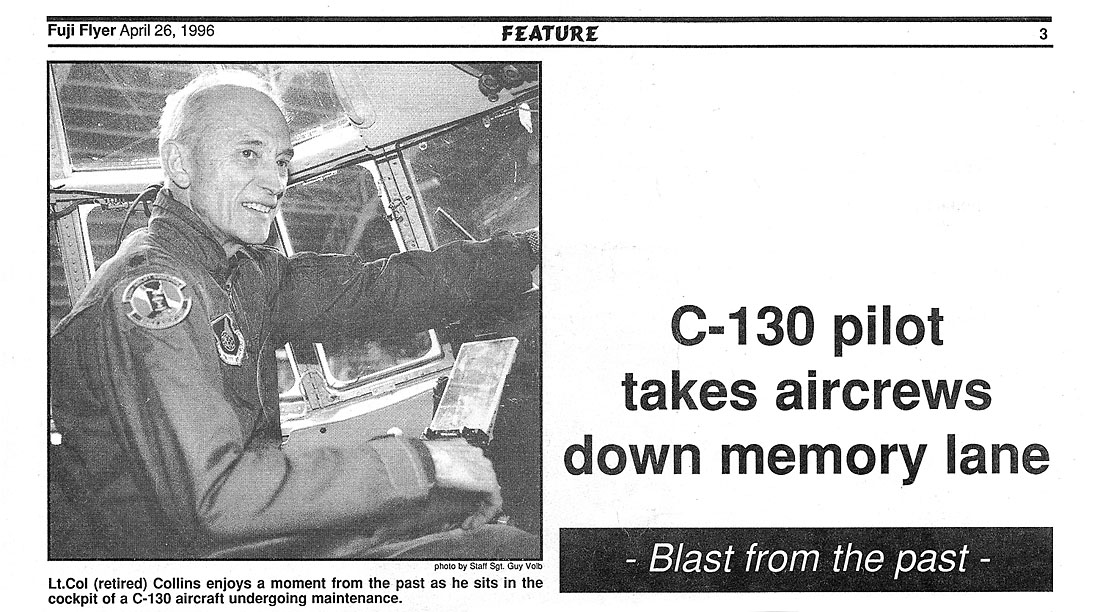

Public Affairs Like a time capsule retrieved after 30 years, Lt. Col. (retired) Phillip Collins resurfaced in his old stomping grounds here this month to share experiences gained from his many years in the cockpit during the infancy of airlift. There was a time in the late 50s and early 60s, he

offered, when being stationed in Japan meant 25-cent haircuts and an enticing

yen rate of 375 to the dollar. During his vacation here the lanky, spry, 63-year-old

Collins spoke to Yokota's airlift crews about his and the C-130's historical

airlift past — complete with the many flight innovations he helped make. Ironically, while many of today's crews

weren't even born when he was flying, the mode of transportation remains the

same — the C-130 Hercules. Collins' journey down memory lane began in August 1956. As

a new graduate of the San Angelo, Texas, flight school, where he flew B-25s,

he was assigned to Ashiya, Japan, where he flew the C-130's predecessor, the

C-119. As a member of the 37th Troop Carrier Squadron, a relative of Yokota's

36th Airlift Squadron, the 37th TCS performed "airlift

missions" much like the 36th and 30th Airlift Squadrons do here now. Following his sixth-month stint at Ashiya, Collins made

his first swing through the local area. He was assigned to what is now Showa

Kinen Koen (Park) in Tachikawa, then

home to the 21st TCS. Once again he

flew airlift missions on C- 119s. But it was in 1959, after the

21st TCS had moved to Naha, Okinawa, when his career made a bee-line for the

history books. With C-130s operational throughout the world, Collins left the Far East for Sewart Air Force Base, Tenn., eventually flying with the short-lived Hercules aerial demonstration team known as the Four Horsemen. He said the C-130 was unique at that time since it handled much like a fighter. |

|

He said the short-runway assault landings were the result

of this disagreement between the Army and Air Force. “At that time,” he said, “there had never been a C-130 to

land on a runway 2,000-feet or smaller. Yet the Air Force said it could be

done — it was a matter of record. So

the Army, thinking it had the Air

Force’s number, basically said put up or shut up.” The Army built a 2,000-foot dirt runway with 50-foot

obstacles on either end of the runway on the range at Eglin. “They said ‘the

Air Force’s tactical documents said you can do it. We built the runway, show

us.’ “Needless to say we’re all looking at each other thinking

‘you’ve got to be kidding, you want us to land on that small runway?’ But the

Air Force said you got to do it, since they said it could be done.” Collins said Lockheed pilots were even sent to Eglin to

show them techniques they felt could be used for short-field landings. “But after seeing them land several

times,” he said, “we felt we needed to come up with our own techniques. They

were driving the plane into the ground and the wing tips were flapping all

over the place. We told the wing commander to send the Lockheed pilots home.”

And he did. So Collins and the other crews developed the assault

landing technique, and many of the exotic delivery systems used to this day

such as the Low-Altitude Parachute Extraction System or LAPES. Then in 1966 he returned to the Far East for a final tour

of Japan, to the 6091st Reconnaissance Squadron here, bringing his

career full circle. It took Collins 30 years following that tour to return to

Japan, but in doing so he gave today’s airlift pilots insight to some early

C-130 history. |

|

|

The Air Force shut us (the four horsemen) down before we became too active,”he said with a chuckle. "But for the year I was at Sewart we were in great demand. "An interesting aside," he said, "was that

we would go out to the flightline and just pick four aircraft. We used any

four the maintenance folks declared operational. There was no special selection process." Collins said they put on a typical

airshow. "We flew close formations, which no longer happens," he said using his hands to describe other maneuvers they used. "We'd fly a diamond formation, arrowhead and we would normally finish the show with a low-level, 300 knot 'bomb burst.' For a big aircraft to perform this back in those days was unusual since there wasn't another four-engine aircraft of that size that could maneuver like that." A year later Collins moved to Dyess Air Force Base, Texas, where he spent four years involved with C-130 ski operations. He would use large ski pads to land on ice and snow in Greenland, more than likely an initiative taken as a result of the cold war. |

Then

in 1964, during his next assignment at Eglin AFB, Fla., events thrust him

into modern airiift history books. As a member of the 4485th Test

Wing, he was one of a few crew members involved with eveloping C-130 tactics,

delivery systems and instrumentation still used today. It

was Collins, and members of eight other crews who completed the first-ever

assault landing on a 2,000-foot runway.

The landing technique which helped them stop in an average of

1,200 feet, is still used today and was important then since ground troops in

Vietnam needed close are support. “Vietnam was beginning to heat up,” he said, “and the Army wasn’t sure the Air Force could provide the technical airlift they needed. They wanted the funding to build their own flying units. But the Tactical Air Command said it could do it and we were going to prove it.” |

||